The New Judy Blume Documentary Illustrates Why I’ve Loved Her…Forever

By Zibby Owens

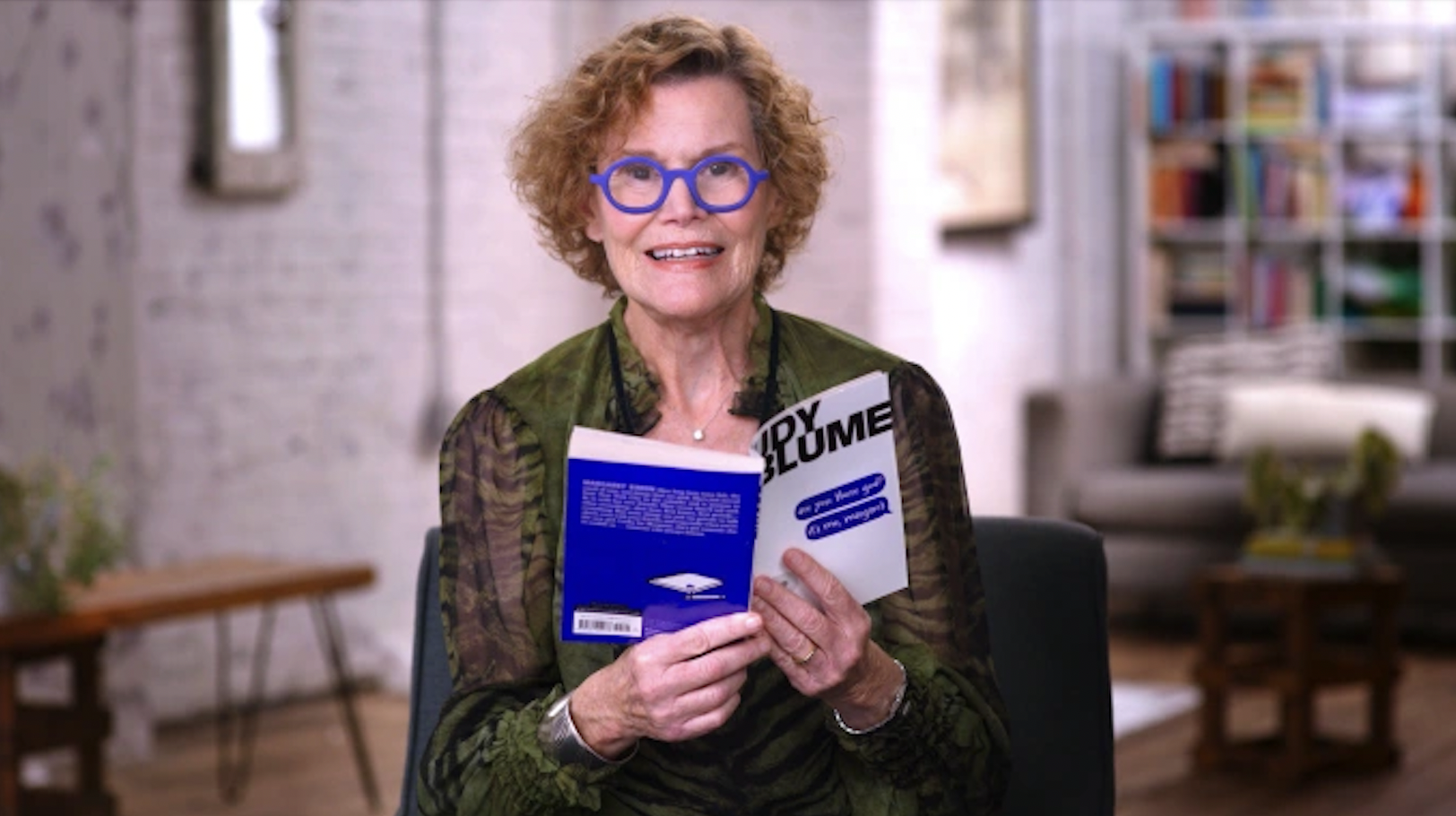

Courtesy of Sundance Film FestivalI thought I knew Judy Blume. Of course, that was foolish.

I thought I knew Judy Blume because—through her characters—she shared what I believed were her innermost thoughts. I thought I knew her because I could recognize her voice anywhere, because I’ve read (I think) every single one of her books, because I could spot her a mile away, and because she has always been a role model to me.

But until I saw Judy Blume Forever, the new documentary about the author, I didn’t realize how little I really knew. Or how much we had in common.

First, some background: Judy grew up in the 1940s just as World War II was ending. While her parents assured her she was safe, as a Jewish girl in the U.S. just across the ocean, she wasn’t so sure. She learned early on that adults didn’t always tell the truth, so she developed a mistrust that lingered. What were the grown-ups hiding? Judy added little anecdotes about concentration camps and Hitler in her earliest works. When the 1950s came around, Judy was one of those daughters of Jewish suburban moms who simply had to be perfect, look perfect, do well at school, please others, and not even think about their own needs. Their burgeoning sexual desires? Ha! Not a chance. Nothing was discussed, clarified, or acknowledged.

Judy harbored an outsized worry about her father’s health. As the seventh child of a family in which no one lived past sixty, Judy’s father was, she feared, next in line. Judy convinced herself as a young girl that if she could just pray hard enough, she could prevent her dad’s early demise. Her dad was the real caregiver in the family, the one who “cut the fingernails” and nurtured Judy and her brother. The thought of his passing away imbued her with an ever-present anxiety.

Like many girls of the 1950s and 1960s, Judy went to college but left early after meeting the dashing lawyer who would become her husband. Five weeks before her wedding, Judy’s father had a massive heart attack and died in front of her. She held his hand as he laid on the floor saying, “S—t, s—t, what terrible timing,” and then died. In a way, she never recovered from that. Her novel Tiger Eyes addressed how she got through that horrific period of grief, ignored by many who loved her, while starting her life as a married woman.

Before she knew it, Judy was back in suburban New Jersey, raising two children, apron on, a smile plastered on her face. And yet she felt different than the other moms. Restless. On the clock. She wanted more. When some other women took to protesting, Judy started writing. At first she wrote children’s books which were summarily rejected—many in very aggressive, bitter letters—before moving on to writing for 11 and 12 year olds.

Not only was Judy remarkably good at capturing what those children thought and felt (so much so that one child wrote her and said “How do you know all of our secrets?”) but she was the first to expose the realities of puberty, sex, and more. Back then, no one was writing about how it felt to get your first period or wish to “develop” on the same timeline as your best friend. There were no blogs. No Instagram. No sisterly advice books. There was, simply, Judy.

It’s no surprise that many of her books were banned for including lines like “Deenie touched her special place.” The idea that girls masturbated was so profane that people demanded the publisher retract the book and that libraries stop stocking her work. Judy took to the media to defend her books and then became deeply involved in anti-censorship organizations.

Meanwhile, Judy got divorced at age 37, and then quickly got remarried and divorced again four years later. Ashamed, she assumed that “love just wasn’t in the cards” for her, until she met George. Forty years later they’re still together.

Judy wrote incessantly and keep nudging up the content to older and older characters. Forever, then Wifey and Summer Sisters, among others.

Back then, no one was writing about how it felt to get your first period or wish to “develop” on the same timeline as your best friend. There were no blogs. No Instagram. No sisterly advice books. There was, simply, Judy.

The beautiful, intimate documentary directed by Davina Pardo and Leah Wolchok highlights the correspondence she kept with many fans, including one whose college graduation she attended when her own parents couldn’t be there. As Judy goes through the archive of letters, now donated to Yale University, fans speak to the camera recounting writing Judy and how her responses saved their lives. Authors like Cecily von Ziegesar, Jason Reynolds, Lena Dunham, and Jacqueline Woodson sit against the floral wallpaper, When Harry Met Sally style, and share their thoughts about Judy and her work. A mix of Judy’s home movies and stock footage highlight the different eras of American history and Judy’s role in all of it.

At the end of the film, Judy goes behind the scenes at her Books & Books store in Key West, an area she unexpectedly fell in love with. She admits she never planned to open a bookstore, but she simply adores it. Why doesn’t she want to write anymore? She just wants to be “out there,” she says, gesturing her arms with enthusiasm. At age 83, having already contributed prolifically to American literature, she now wants to have a life away from her keyboard.

What Judy Blume did that was so life-altering was write authentically about human emotion, something that instantly connected readers. She didn’t do it in an exhibitionist manner. She did it to help and heal, both herself and others.

Like Judy, I grew up a Jewish girl, deeply attached to her dad who, although he didn’t “cut the fingernails,” sustained me emotionally. I also loved to write and, in fact, corresponded with another author, Zibby O’Neal, for years, which led to her coming to New York and taking me to tea at the Plaza when I was in fifth grade. I must have written to Judy Blume, too. If I dive into the archive at Yale, I’m sure I’ll find my own words alongside the words of so many others who became authors themselves.

Like Judy, I felt pressure to be perfect, to please, and to be a good girl. I got married and divorced, although only once, and faced publishing rejection before eventual success. I also learned about the power of authentically sharing my thoughts early on. My first personal essay—about gaining 20 pounds after my parents’ divorce and my proceeding body-image struggles—was published in Seventeen magazine when I was 16 years old. According to the editors, it got more fan mail than any article they’d run recently. Fan letters were printed in subsequent issues of the magazine and sent to me in droves. I quickly learned that when I shared openly, from the heart, I could help others. I haven’t stopped since.

More similarities? At times, I also feared a big love wasn’t “in the cards” for me, until I unexpectedly met my husband, Kyle. I didn’t lose my father like Judy, but I experienced grief at the same age when I lost my best friend. And, like Judy, I now own a bookstore.

I can’t compare myself to Judy without some self-consciousness. I am nothing like her; she is a national treasure. A genius! But I know that when I share things about myself—the internal monologue, the things I feel ashamed to think and feel, the worries—other people can see themselves and we all feel less alone. Perhaps I learned that from Judy without even realizing it.

Thank you, Judy Blume, for rethinking what literature can do for the soul and for reminding us that we are all deeply human with a shared set of emotions, hopes, fears, insecurities, love, worries, and shameful secrets which, when unearthed, connect us. Thank you for being a true role model for young girls who read your novels and fantasized about becoming an author like you. Thank you for showing us that this could be a career, and that women’s words, even when not the most esoteric or literary, could be highly valued. Thank you for proving that telling it like it is does a lot of good.

And, finally, thank you for pioneering authenticity in literature and for helping so many people for so many years. If only we could all take a page out of your book, imagine how wonderful that library would be.